Extent and Distribution

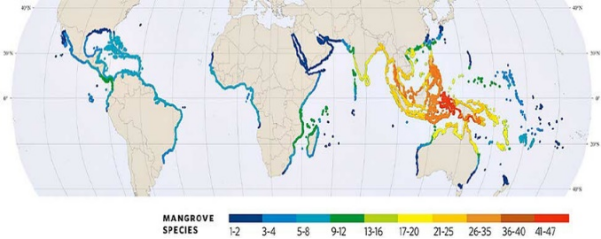

Mangroves are restricted to 30° North and 30° South latitude. However, the most northernly mangroves are located at 31°22.5’ N near the town of Kiire of Japan in the northern hemisphere and most southerly mangroves are located at 38°45’ S of Australia, where the mangroves exist below freezing point. ... Generally, mangroves dominate on the coast and the river banks up to which the tidal water ingress during high tide in the tropical and sub-tropical regions. The distribution pattern of mangroves is the result of latitudinal limit; particularly sea surface temperature, air temperature and inland rainfall. Globally there are two main centres of diversity of mangrove communities, the western and the eastern groups (Tomlinson, 1986). The eastern group correspond to the Indo-West Pacific regions which include central Pacific, East Africa, Indo-Malayan and Australasia. The western group correspond to Atlantic East Pacific regions which include the West African and American coasts of the Atlantic Ocean, the Caribbean Sea, the Gulf of Mexico and the western (Pacific) coast of America. These two regions have different floristic inventories. The Indo-West Pacific region has higher mangrove diversity, i.e. five times more diverse compared to the Atlantic East Pacific region.

Global Mangrove Cover

The total mangrove cover area of world is 152,361 sq. km (Giri et al., 2011). The mangrove cover has greatly decreased since the last century. Globally, it comprises less than 1% of tropical forest cover and 0.4% of total forest cover of world (FAO, 2006). ... Mostly mangroves are dominantly tropical forests and are found in the tropical region of South-east Asia, south Asia, North and Central America, South America, West and Central Africa and south Asia.Among them maximum area of mangroves is found in South-East Asia region over an area of 52,049 sq. km followed by South America region with 23,882 sq. km, North and Central America region with 22,402 sq. km and West and Central Africa region with 20,040 sq. km. The least mangrove cover is found in the Middle East with 624 sq. km.Figure 1.2. Pi chart showing mangrove cover in different regions.

In political perspective mangroves are found in 123 countries worldwide among which 12 countries comprise nearly two thirds of mangrove cover. Indonesia has maximum mangrove cover comprising 20.9 % of world total mangrove cover. Next to Indonesia, Brazil, Australia, Mexico, Nigeria, Malaysia, Myanmar, Bangladesh, Cuba, India, Papua New Guinea and Columbia have mangrove cover in descending order area wise (Table 1.1).

Table 1.1. Twelve countries with the largest mangrove area in the world, altogether comprising 68 percent of world’s total mangrove.

| Country | Mangrove Area (sq.km) | Proportion of Global Total |

|---|---|---|

| Indonesia | 29.9 % | |

| Jacob | 8.6 % | |

| Australia | 6.5% | |

| Mexico | 5.0% | |

| Nigeria | 4.8% | |

| Malaysia | 4.7 % | |

| Myanmar | 3.3 % | |

| Bangladesh | 3.2 % | |

| Cuba | 3.2 % | |

| India | 2.8 % | |

| Papua New Guinea | 2.8 % | |

| Colombia | 2.7 % | |

| Rest countries | 22.5 % |

MANGROVE SPECIES DIVERSITY

Mangroves represent a large variety of plant families, which are adopted to tropical inter tidal environment. Although mangrove is considered as tropical ecosystem unlikely other tropical ecosystems the diversity of mangroves is very low. Different researchers have classified mangroves in different classes taking different criteria. Saenger et al (1963) have classified mangroves into exclusive mangroves and non-exclusive mangroves based on mangroves habitat as well as elsewhere. He has considered 60 plants as mangroves out of which 48 are kept in exclusive mangroves group and rest in non-exclusive mangroves group. Tomlinson (1986) has classified mangroves in three groups based on exclusive position of plants in the estuary and other habitats such as (1) Major elements of mangal ('strict or true mangroves') (2) Minor elements of mangal and (3) Mangrove Associates. The major elements of mangal ('strict or true mangroves') possess all or most of the following features:- Complete fidelity to the mangrove environment; that is, they occur only in mangal and do not extend into terrestrial communities.

- A major role in the structure of the community and the ability to form pure stands.

- Morphological specialization that adopts them to their environment; the most obvious are aerial roots, associated with gas exchange and vivipary of the embryo.

- Some physiological mechanism for salt exclusion so that they can grow in sea water.

- Taxonomic isolation from terrestrial relatives. Strict mangroves are separated from their relatives at least at the generic level and often at the subfamily or family level.

The minor elements of mangal are distinguished by their inability to form a conspicuous element of the vegetation. They occupy peripheral habitats and only rarely form pure communities. The Mangrove associates however, do not inhabit in habitat of strict mangrove communities, and may occur only in transitional vegetation and even exist as epiphytes. Based on above criteria Tomlinson has kept 34 species of 9 genus from 5 families under major elements mangrove, 20 species of 11 genus from 6 families in minor elements of mangroves.

Duke (1992) defines true mangrove more specifically as “a tree, shrub, palm, or ground fern generally exceeding 0.5 m in height and normally grows above mean sea level in the intertidal zone of tropical coastal or estuarine environments”. He has prepared an improve list of 69 mangrove species in 20 genera and 16 families in the world.

Kathiresan and Bingham (2003) have prepared a list of 65 species of 22 genera from 16 families which include Tomlinson's major and minor elements but not mangrove associates. They did not include three shrubby species; Acanthus illicifolius, Acanthus ebracteatus, Acanthus volubilis and two palm species; Nypa fruticans and Phoenix paludosa.

Most recently Spalding et al. (2010) in “World Atlas of Mangroves” have considered 73 species and hybrids as true mangroves. All these species have adopted to mangrove habitat. Out of 73 mangrove species, 38 species are considered as core species which typify mangroves and dominates in most mangrove ecosystems. The rest others are rarely abundant and more appropriately found on fringe of the mangrove habitats.

Polidoro et al. (2010) have considered 70 species as true mangrove based on Tomlinson's original list of major and minor mangroves supplemented by a few species added through the expanded definition provided by Duke (1992) and other new taxonomic additions by Sheue et al. (2003; 2009). This book follows Polidoro et al. (2010) list of mangroves. The list of true mangroves is given below (Table 1.2).

COUNTRY WISE MANGROVE DISTRIBUTION

Mangrove species distribution is not uniform worldwide. Maximum true mangrove species richness is found in South Asia, South-East Asia, Australia, New Zealand and Pacific Islands. ... Among the countries Indonesia has the maximum true mangrove species richness followed by Papua New Guinea, Philippines, Malaysia, Australia, India and Thailand.Mangrove cover of India for last one decade

The Sundarban on delta of the Ganges and the Brahmaputra of West Bengal accounts more than 40% of mangrove cover of India over an area of 2114 sq km. Gujrat has 2nd largest mangrove cover in the country over an area of 1140 sq km, followed by Andaman & Nicober Islands with of 617 sq km, Andhra Pradesh with 404 sq kms, Maharastra with 304 sq km and Odisha with 243 sq km of mangrove cover (FSI Report – 2017). In India the mangrove area is increasing over the years.Pi Chart showing mangrove cover in percentage state and Union wise.